-

First Intel-Powered Convergence Device Being Unveiled in Europe

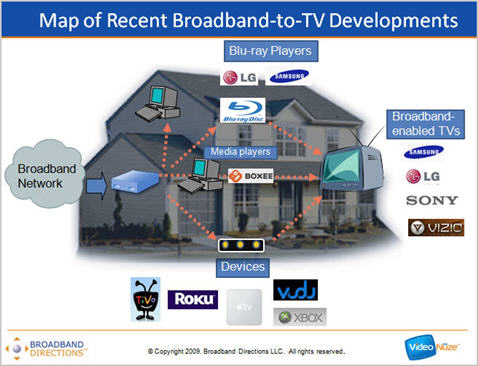

Convergence devices that bring broadband video and Internet applications to the TV (e.g. Roku, Xbox, Apple TV, Vudu, etc.) are a white-hot area of interest as many industry participants - including me - believe their eventual mass adoption will provide a major catalyst to broadband video usage and prompt further disruption in the value chain.

Intel has eyed a big role in this emerging market for a while, becoming a strong public proponent of the "digital home" concept. Building momentum over the past year, Intel has made announcements with Yahoo (for the "Widget Channel" framework), Adobe (to port and optimize Flash for TV viewing) and with a number of large content providers (demonstrating enhanced viewer experiences).

At the heart of Intel's early initiatives is the company's much-heralded Media Processor CE3100, the first in a family of "system on a chip" convergence-oriented processors. Next week the first CE3100-powered device, the "Mediaconnect TV" will be shown at the IBC show in Amsterdam. The box is a collaboration between a Dutch company, Metrological Media Innovations and a British interactive services provider, Miniweb (a spinoff of BSkyB). This has been previewed recently and is sure to gain more visibility next week. To learn more about Intel's convergence vision, yesterday I spoke to Wilfred Martis, the GM of Connected AV Products for Intel's Digital Home Group.

Intel sees 4 different types of home products that can be fitted with its media processor chips: set-top boxes, digital TVs, optical players (e.g. Blu-ray devices) and "connected AV" products, which are defined as standalone boxes that connect broadband to the TV, but without any guaranteed quality of service (QoS) for the video. This segmentation actually closely follows a slide I've been presenting lately which maps the various efforts for bringing broadband to the TV.

The connected AV devices are of course what "over-the-top" providers like Netflix, Amazon, iTunes, YouTube, etc. are counting on to deliver their services into the home over open broadband connections. On the one hand, Intel seems to be looking to empower these providers. As Wilfred says, Intel is trying to create a standard toolset and app environment akin to what we've seen on leading smartphones (mainly the iPhone) that helps drive creative new TV-based applications. Yet at the same time, as Wilfred notes, Intel wants to be a friend to incumbent video service providers, allowing them to deliver broadband content side-by-side with their walled-garden channels in their set-top boxes.

While Intel is clearly in this for the long haul, and has the resources to cultivate the market, other non-Intel devices continue to get a foothold. It's interesting to contrast, for example, the success that Roku is enjoying to date and ponder how the convergence device market will develop over the next several years. As I detailed a few weeks ago, Roku is successfully pursuing a classic "Crossing the Chasm" strategy, leveraging low pricing and loyalty to its content partners' brands to move lots of its product.

Still, integrating with Roku - and other current convergence devices - requires a one-off integration that assumes resources and prioritization (even when APIs exist). Some content providers will determine integrating is worthwhile, while others will not.

Intel's strategy is meant build on existing technologies and applications, making it more straightforward for content providers and applications developers to deploy on its devices (it's worth noting that Amazon, Blockbuster, Facebook and others plan to launch Widget Channel apps imminently). As Wilfred explains, when Intel's architecture is in convergence devices, incumbent software like browsers, plug-ins, drivers and the like are intended to work seamlessly. In addition, by providing abundant processing power, developers don't have to go through the arduous task of de-optimizing their apps for slower environments. And they get the performance headroom to continuously add updates.

The price for all this is of course, price. I don't know what the unit cost of the CE3100 is at volume, but my guess is that whatever it is would quickly sink any manufacturer's prospects of selling their box at anything close to a $99 price point, as Roku is. It's an age-old computing dilemma: beneficial as it is to have lots of processing power, there's a cost to it.

This raises the fundamental question of how the convergence device market will shape up over the next several years: will low-cost, "powerful-enough" devices continue to gain, or will boxes with robust processing render them obsolete at some point soon? My guess is that in the short term at least, low cost is going to lead the way. However, over the long term, it's hard to avoid the idea of significant computing power sitting next to the TV. However the business model for who pays to get it there remains in question.

What do you think? Post a comment now.

Categories: Devices, International

Topics: Adobe, Intel, Metrological Media Innovations, Miniweb, Roku, Yahoo