-

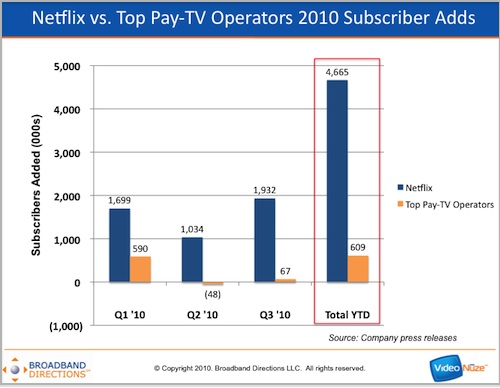

Netflix Has Added 8 Times As Many Subscribers in 2010 As Top Pay-TV Operators, Combined

Here's a pretty amazing factoid to end your week: in 2010 Netflix has added nearly 8 times as many subscribers as 8 of the top 9 pay-TV operators have, combined (#3 cable operator Cox is private and doesn't report). In the first 3 quarters of 2010, Netflix has added nearly 4.7 million subscribers while the top pay-TV operators have gained 609K.

Breaking down the pay-TV industry net gain further, the 2 main telcos (Verizon and AT&T) have added over 1.2 million subscribers and the 2 main satellite providers (DirecTV and DISH) have added 563K, while the top 4 reporting cable operators (Comcast, Time Warner Cable, Charter and Cablevision) have lost over 1.1 million.

Netflix is following what Clayton Christensen, in his book, "The Innovator's Dilemma" calls a classic disruptor's strategy: offering an underperforming product relative to incumbents' that includes new features incumbents' products don't. In Netflix's case, it doesn't offer any live, or even highly current, content, making it inferior to pay-TV services in this respect (particularly notable in sports). However it does offer higher convenience through integrations with dozens of inexpensive connected and mobile devices, deep content selection, unlimited viewing and a superb user experience.

As I noted in my post about overall Q3 pay-TV performance, in 2010 Netflix has used its $9/mo entry tier to seize the low-cost/value-oriented market opportunity. In this way it has done something else right out of Christensen's book - taken advantage of incumbent pay-TV operators' "overshooting the market," meaning giving subscribers more than they actually desire (and are increasingly unlikely to pay for). Pay-TV operators' overshoot is the lengthy list of channels now delivered, which have driven up operators' costs, and in turn their rates. Even as all research shows that only a cluster of 6-8 channels are watched consistently by any individual viewer, operators have continued to deluge subscribers with new ones, many of which are barely even known. In effect, more channels are often actually perceived as delivering less value ("hence the "500 channels and nothing on" concept).

To be fair, pay-TV operators' are about more than just video, and their average revenue per subscriber dwarfs Netflix's. For example, Comcast's Q3 ARPU of $129.75 is at least 10 times Netflix's $12.12 (my calculation) and Cablevision's $149.04 over 12 times as much. The pay-TV operators have multiple services - digital tiers, HD, DVR, broadband Internet, voice, etc. and have been very smart about bundling services to create a lock-in effect.

With Netflix likely to end the year with close to 20 million subscribers, 2nd-only to Comcast, the question should not be if, but when, pay-TV operators will introduce lower-priced tiers to blunt Netflix's appeal. So far, only Time Warner Cable's CEO has alluded to such plans, and given the complex programming contracts, doing so may not even be possible. Meanwhile, the industry's tentative embrace of "premium VOD," where movies are rented for $30-40 apiece strikes me as moving in exactly the wrong direction. If you're the high-cost provider and a low-cost competitor is gaining ground, what sense does it make to move further upstream? The smart pay-TV strategy is TV Everywhere, which is meant to deliver the full menu online. As I've argued, it is imperative to the industry that TV Everywhere rollouts be on the fast track.

In the coming quarters, the pay-TV operator industry will be dealing with a brave new world being brought on by online video delivery. We'll see how well they meet the new challenges.

What do you think? Post a comment now (no sign-in required).Categories: Aggregators, Cable TV Operators, Satellite, Telcos

Topics: AT&T, Cablevision, Charter, Comcast, Cox, DirecTV, DISH, Netflix, Time Warner Cable, Verizon